Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night)

2 Violins, 2 Violas, 2 Cellos

30 Minutes

About the Composer

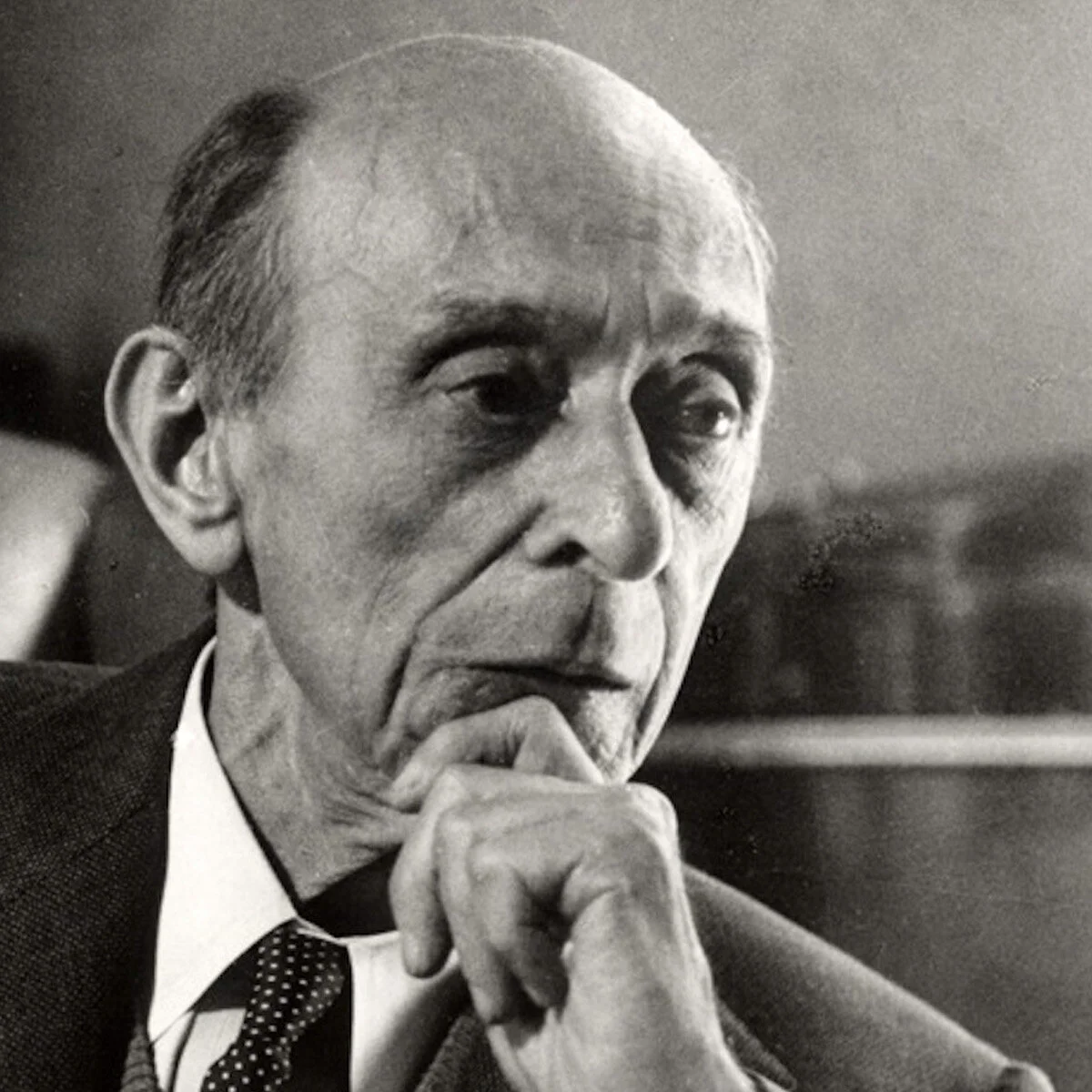

Arguably one of the most influential 20th century voices, Austrian composer and painter Arnold Schoenberg was born in Vienna on September 13, 1874 to a lower middle-class Jewish family. Schoenberg was pioneer of the expressionist movement and the leader of the Second Viennese School, which included his pupils Alban Berg and Anton Weber. Schoenberg’s music expanded late-Romantic chromaticism, evolved into free atonality, and later developed serial twelve-tone technique. His musical instruction began young on the violin at age eight, and very soon after he began composing. He was largely self-taught and took only counterpoint lessons with composer Alexander Zemlinsky. In 1898 Schoenberg converted to Christianity in the Lutheran church. Scholars claim this decision was partly to strengthen his attachment to Western European cultural traditions, and partly as a means of self-defense in a time of resurgent anti-Semitism. Throughout his life he moved around Europe quite a bit, spending a number of years in Berlin. In 1933 he left Berlin for France—due to the increase in anti-Semitism as Hitler rose to power—there he reclaimed his Judaism in a Parisian synagogue. One year later in 1934, he emigrated to the United States.

Schoenberg made his was to his eventual home in Los Angeles by way of Boston, where he taught and lectured for about a year. In 1936 he was named a professor at UCLA, and while in LA he formed a lasting friendship with George Gershwin, the legendary American composer of Rhapsody in Blue. In 1941 Schoenberg became an American citizen. He continued to teach at both UCLA and USC until he died in 1951, influencing countless students from Dave Brubeck to John Cage, and leaving a significant and lasting mark on the ethos of American classical music.

Arnold SCHOENBERG

About the Music

One of his early works, Verklärte Nacht (“Transfigured Night”), tells of a miraculous transformation; however, it is not truly the night that is altered but, rather, the emotional and spiritual state of a woman, from despair to hope, grief to joy, through an act of love. Schoenberg composed the work in 1899 as a string sextet inspired by a poem by the German fin-de-siècle writer Richard Dehmel. The narrative tells the story of a couple who while walking through the woods at night, affirm their relationship to one another despite the fact that the woman is carrying the child of another man. Aptly, Schoenberg’s musical language—which marries expressive liberties of Wagnerian chromatic harmony with Brahms’s developing variation technique—mirrors the emotional complexity of Dehmel’s journey. For a performance of the work in New York in the 1920s esteemed American music critic and scholar, Henry E. Krehbiel paraphrased the text:

"Two mortals walk through a cold, barren grove. The moon sails over the tall oaks, which send their scrawny branches up through the unclouded moonlight. A woman speaks. She confesses a sin to the man at her side: she is with child and he is not its father. She had lost belief in happiness and, longing for life's fullness, for motherhood and mother's duty, she had surrendered herself, shuddering, to the embraces of a man she knew not. She had thought herself blessed, but now life has avenged itself upon her, by giving her the love of him she walks with. She staggers onward, gazing with lackluster eye at the moon which follows her.

"A man speaks. Let her not burden her soul with thoughts of guilt. See, the moon's sheen enwraps the universe. Together they are driving over chill waters, but a flame from each warms the other. It, too, will transfigure the little stranger, and she will bear the child to him and make him, too, a child. They sink into each other's arms. Their breaths meet in kisses in the air. Two mortals walk through the wondrous moonlight."

While the work is one movement, nearly thirty minutes in length, it can be divided into five distinct sections, which relate to the five stanzas of Dehmel’s poem, and thus mirror emotional transcendence. The themes in each section are direct musical metaphors for the narrative discourse found in the poem. The work begins with a mournful falling theme in the low strings that eventually becomes agitated, resigned, compassioned, and ecstatic before finally closing with an ineffable tenderness.